The list is here because it contains some seminal works on popular music. Feel free to ignore the tomes on social justice if you didn't ask for my opinion on such things.

In chronological order of reading, best as I can remember.

Take Wing; Jean Little: Even though there were other (visibly) disabled kids in my class, I felt I was the only one. Jean Little's best book, about a girl with a learning-disabled brother, made me realize that other kids coped with disability -- and were desperate to hide it. Take Wing hit me like a bomb. It is, hands down, the book that made me love reading, way back in fourth grade.

The Poetry Of Rock; I was a classically-trained flautist who didn't start singing until she was fifteen. What I didn't know about the crucial importance of lyrics, this book taught me. It would be decades before I could explicate this way of thinking to others. Side note: My copy of this is dissolving as I write.

That Man Cartwright; Ann Fairbairn: Two lessons -- wait, no, three -- I learned from this book: One: Change will never come about if you only hang with the, er, cool people, or those who think like you. Two: Going along to get along exacts a terrifying cost that everyone in your orbit ends up paying. Three: Justice for farmworkers means justice for everyone who consumes the fruits of their labor. This is true in the most concrete and immutable way possible. Don't believe me? Read this book, then think hard -- really hard -- about the constant spate of produce recalls we see today.

The Rolling Stone Record Guide; Various: As much as I hated Rolling Stone's chest-pounding, provincial style, the magazine -- and, by extension its first record guide -- introduced me to a way of writing about music that directly impacts my work today. Despite what crabby commentators like Steve Allen said, rock and roll could often be counted on to reveal a rich inner life and exceptional cultural literacy; as well as an activism informed deeply by established knowledge and lived experience, on the part of its creators. Attention must be paid, they insisted. I haven't stopped paying attention since.

The Name Is Archer; Ross MacDonald: I didn't have to read books to know that some people did evil because it was fun (The First Deadly Sin, Lawrence Sanders). I didn't have to read books to know that a parent could be the devil incarnate (Iceberg Slim's Mama Black Widow). I didn't have to read books to know that kids could be thrown in the trash because it was convenient (Bel Kaufman's Up The Down Staircase, Stephen King's Carrie). I did have to read a book to know that, somehow, somewhere, there were adults who gave a rip. And I had to read it over and over again. This collection of short stories, featuring detective, Lew Archer, yet another survivor of a rough childhood, was that book. I've only just now remembered that I found it because someone in Rolling Stone mentioned MacDonald's heart for maltreated kids, as expressed in the California-centered Lew Archer stories. I have no idea who that person was, but I am eternally grateful.

Tales From A Troubled Land; Alan Paton: From the days when art and literature from South Africans of color (U. of Chicago prof, Denis Brutus, was a notable exception) weren't getting through to the States. South African-raised Englishman, Paton, avoids the privileged-yet-earnest white activist traps of broad characterization, either/or thinking, and sweeping generalization. Paton knows the emotional terrain because he lived with and loved deeply South Africa's people of color. Their experiences were his unshakable, true north, and his writing taught me never to accept anything less from my own. Today's activist authors rely on The Times (pick a major, metro area) and NPR for their talky, tired, impotent change-being. They get book deals and literary prizes for it, too. Paton puts them all to shame.

Gentlemen's Agreement; Laura Z. Hobson: More than just how bigotry looks, Gentlemen's Agreement is about how bigotry thinks -- and, in the most rarified circles. It helped me home in on the qualities of human interaction on race and creed that just seemed ... off. Surprisingly, for a book about ideas, this is a book of profound humanity. Surprisingly, for a book about a bunch of New York swells, it's a book that stays blessedly down to earth.

Fahrenheit 451; Ray Bradbury: Censorship? No. Fahrenheit 451, first published in 1953, is about the consequences of thinking -- and doing -- for yourself in the age of Internet and reality TV. Shatteringly prescient.

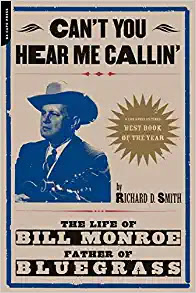

Can't You Hear Me Callin'; Richard D. Smith: I was not a fan of musical biographies. Even the high-falutin' ones seemed to focus exclusively on their subjects' sex lives in order to obscure the authors' inexcusable ignorance of the fundamentals of music, and of creativity itself. Not so Richard D. Smith's towering biography of the Father of Bluegrass Music, Bill Monroe. Smith understands Monroe's earth-shattering, musical creation in a way that bluegrass musician/authors like Neil Rosenberg, and musical dilettantes like Ted Lehmann and Kim Ruehl of No Depression fail to do to this day. Are the sex, the soap operas, the struggles, and the spite still here? Yes, they are, in authoritative detail. But, if you want to understand bluegrass music better than anyone else on the festival circuit, there is no other -- or better -- book.

The Bible: Right. Don't @ me. See, if someone spends your childhood telling you that you must live by this book, or perish; if, decades later, you discover that a bunch of someones spent your childhood lying to you about what's in this book you must live by, or perish; when you finally read the entire book for yourself, it is life-changing. In my case, so much so that I now live by an almost entirely-different set of rules than those with which I grew up.

No comments:

Post a Comment